Polar clouds can tell us things we don’t know—but should know—about the climate of the future.

CLOUDS ON THE HORIZON Fewer and fewer Antarctic petrels are finding their way from the coast up into the mountains around the Norwegian research station Troll in Dronning Maud Land. Over the last twenty years, the petrel population in this area has declined sharply; this decrease is linked to warming oceans, extreme weather and failing food supplies. Photo: Stein Tronstad / Norwegian Polar Institute

Sunshine and clear skies are many people’s idea of summer perfection—but did you know that the gray clouds that roll in from time to time play a critically important role in keeping our planet habitable?

About 5 Degrees Warmer Without Clouds

– Clouds reflect sunlight before it reaches the ground, reducing temperature both locally and globally. They also act like blankets that trap heat, raising surface temperature. Locally, it’s the balance of these two effects that shapes weather and climate.

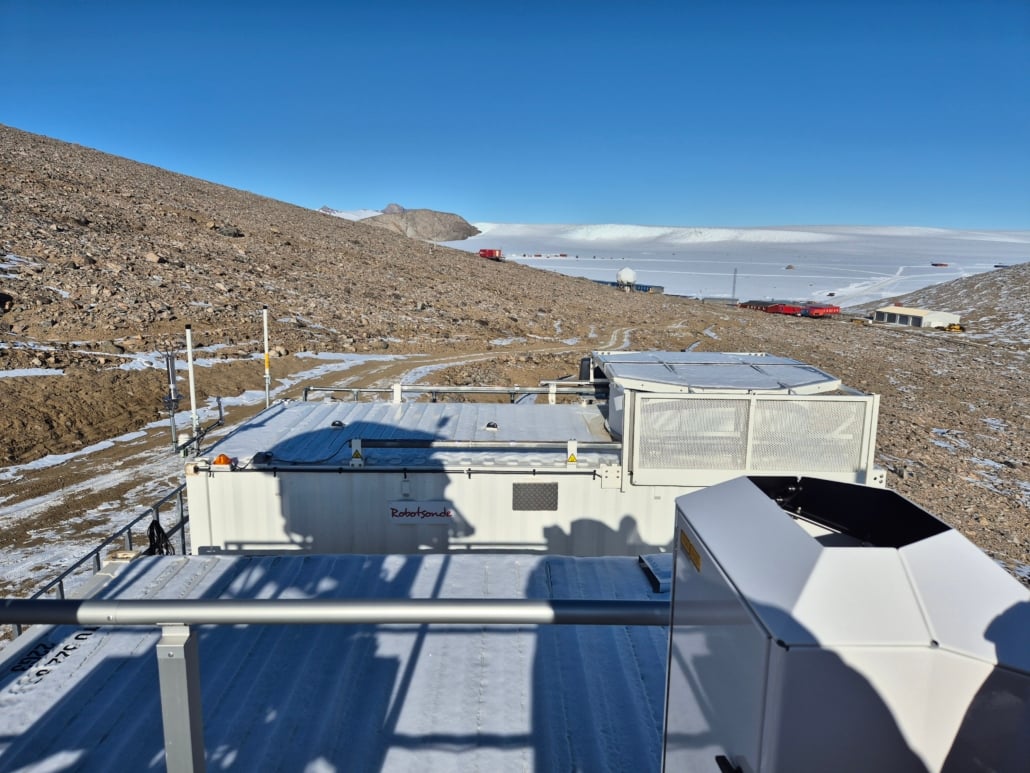

CLOUD OBSERVATORY AT TROLL For the first time, clouds can be studied from Troll. The integrated cloud observatory was completed earlier this year thanks to dedicated efforts by staff from the Polar Institute and partner institutions. Photo: Stephen Hudson / Norwegian Polar Institute

Amplify or Dampen?

See the first balloon launch from the Troll cloud observatory

DAILY BALLON LAUNCH The cloud observatory launches one weather balloon per day, all year round. Each balloon carries a radiosonde that measures temperature, humidity and wind up to 30 km in the atmosphere. Very little such data exist from this region, but we desperately need it—researchers already see signs of climate change here in Dronning Maud Land. Photo: Norwegian Polar Institute

Uncharted Territory

LEADING THE CLOUD RESEARCH –The goal is for the weather balloons and other instruments to give us more knowledge about the atmosphere over and around Troll, and especially about the role clouds play in the climate puzzle in Dronning Maud Land, says researcher Stephen Hudson of the Norwegian Polar Institute. Photo: Natalie Snyder

Mixed-Phase Clouds May Hold Answers

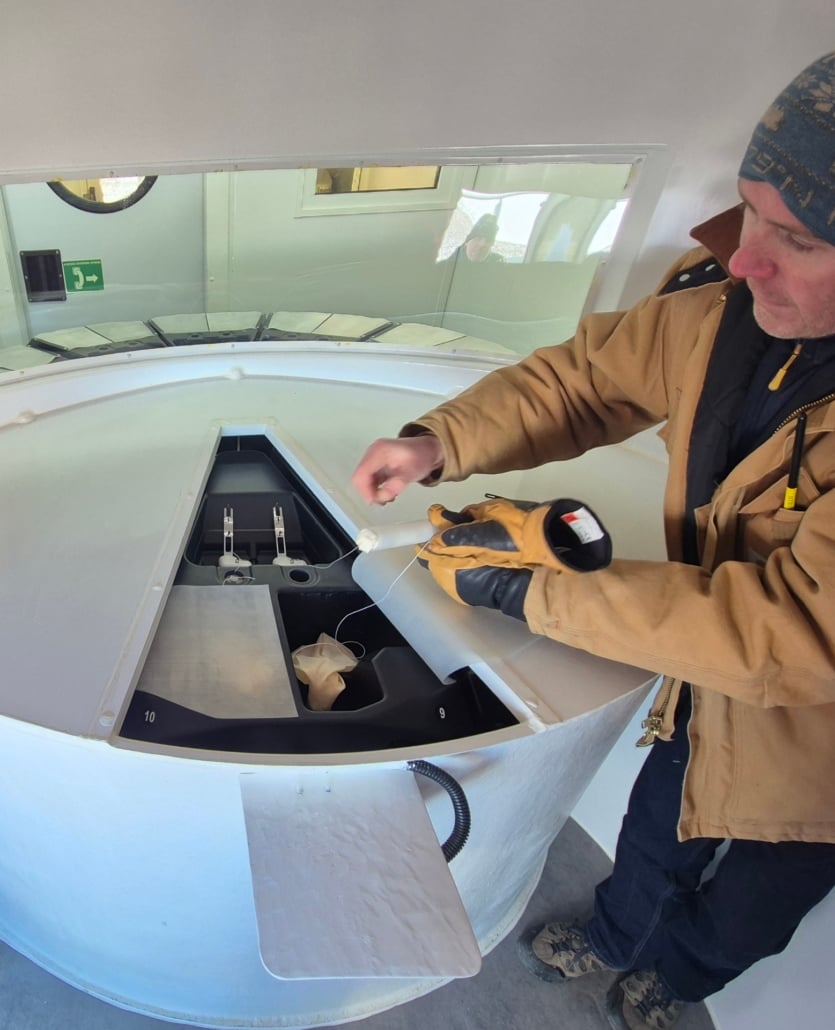

FIRST BALLON FLIGT Stephen Hudson prepares for the first balloon launch from Troll. Photo: Erland Loso / Norwegian Polar Institute

When clouds contain more water droplets and fewer ice crystals, they reflect more sunlight and emit more infrared radiation toward the surface.

TEAM AT THE OBSERVATORY The team that helped set up the cloud observatory: from left, Senior Engineer Marius Bratrein and Researcher Stephen Hudson (both from the Polar Institute), with scientists Ryan Neely III (University of Leeds) and Mike Town (Earth & Space Research). Photo: Hans Fredrik Aaby

Rising to the Skies in Search of Knowledge

OBSERVATORY NETWORK The cloud observatory with Troll Research Station in the background. The observatory is part of the Troll Observing Network (TONe), which includes eight observatories collecting long-term time series on the entire Earth system — all established at and around Troll Research Station. Photo: Erland Loso / Norwegian Polar Institute

VALUABLE DATA –The cloud observatory will become a polar flagship activity for Norway in Antarctica. – Much of the other research, monitoring and mapping we conduct in the south takes place not at Troll but out in the field. With the cloud observatory, we now have a presence at Troll as well, says TONe project leader Christina Alsvik Pedersen. Photo: Norwegian Polar Institute

Into Climate Models

INTERIOR OF ANTARCTICA Troll station and the cloud observatory (in front) lie about 235 km from the coast, at Jutulsessen in Dronning Maud Land, and operate year-round. In winter, Troll is run by its six winterover crew; in summer, many more people staff the station and its surrounding areas. Photo: Stephen Hudson / Norwegian Polar Institute

Clouds and Climate

- Clouds consist of tiny water droplets or ice crystals, or a combination of both, and most often form when moist air rises and cools.

- There are many different types of clouds. Some lie right at ground level (fog), while others float high in the atmosphere.

- A warmer climate can influence what types of cloud cover we get, and cloud cover in turn can influence the climate.

- Low, dense clouds reflect a lot of sunlight and can have a cooling effect on the climate.

- Thin, high clouds can trap infrared radiation from the Earth, leading to warming.

- Changes in cloud cover can affect global warming, with consequences for vital resources such as agriculture and solar energy.