Its relative, the brown bear, hibernates in winter to save energy when food is scarce, but not the polar bear. The polar bear eats seals that it can hunt on the ice throughout the year and so has no need to hibernate. Pregnant female polar bears, on the other hand, dig warm maternity dens in the snow in late autumn, give birth to cubs in mid-winter, and remain in the den until March-April.

The cubs are small and hairless at birth, and would quickly freeze to death out in the Arctic night. The cubs grow fast, from about half a kilogram to about 10 kilograms, before they are ready to leave the den in spring. In the spring, when the cubs are two years old, they are weaned. Bears give birth to cubs every three years, assuming that the cubs survive. But many cubs die, so bears den more often than this on average.

Since only pregnant females den, we acquire a lot of data on reproduction from the satellite collars they are fitted with. A lot of data on den ecology is also available from direct observations, which is easier in Svalbard than in many other places, because of the high density of the dens.

What can we read from the collar?

[caption id="attachment_28887" align="aligncenter" width="682"] The figure shows speed (km / h), temperature (measured in the collar, which is affected both by temperature in the air and by the polar bear) and activity (head movement).[/caption]

The figure shows speed (km / h), temperature (measured in the collar, which is affected both by temperature in the air and by the polar bear) and activity (head movement).[/caption]

When a polar bear is in a den during the winter, GPS will record the same position over time ( movement will be 0 km / h). Temperature will be significantly warmer than outside, and almost always measured to> 0 ̊C. Activity is measured by head movement, and is much lower in a female who is mostly at rest inside the den than a female who hunts out on the ice. Thus, from these data from a collar, we can say if, and when, a female is in a den in the winter.

This female bear sent data for three years (orange vertical lines are for May 1 each year from 2014 to 2017). She went into the den in November 2014, probably gave birth to two cubs in December, and left the den in early April 2015. Because she did not go into the den for the next two years, there is a high probability that at least one of the cubs survived.

What do polar bears need from a den?

Two things are important to polar bears when selecting a suitable denning site. Pregnant bears must be able to access the den area without expending too much energy, and there must be sufficient snow (ideally a few metres deep) in the area in autumn, so that the den can be dug out and will be well insulated.

In Svalbard, it is dry and little snow falls in winter. But it is very windy. Svalbard also has a lot of hilly terrain, with steep mountainsides and large plateaus.

Typical terrain suitable for dens, where deep snow drifts form. Photo: Øystein Overrein / Norwegian Polar Institute

When it snows and the wind blows, most of the snow on the plateaus is carried over to the leeside under the steep overhangs. Here the snow may lie several metres deep even in snow-poor winters. Often this snow does not melt away over the summer and the bears dig into the old snow in autumn and then extend the den as newer snow settles in winter. In fact, a den will move continuously upwards during the four-five-month denning period.

Inside the den, the temperature will be above freezing, since the bear emits heat and the snow insulates very well against the cold outside. Ice is therefore formed on the ceiling of a den.

Despite popular belief, the polar bear does not sleep for days in the den in a state of hibernation. If she did, she would probably die from oxygen depletion. Every few days, she scrapes away ice from the ceiling to allow oxygen to enter. A separate air vent can often be seen in the den’s ceiling.

The female polar bear does not go into hibernation, but lowers her body temperature by a degree or two, thereby reducing her energy needs. This is important because she will have to spend almost five months without food and, for maybe three of these months, produce fat-rich milk for one or two cubs. A female weighing over 200 kilograms in autumn may well be down to 130-140 kilograms when she leaves the den at the end of March.

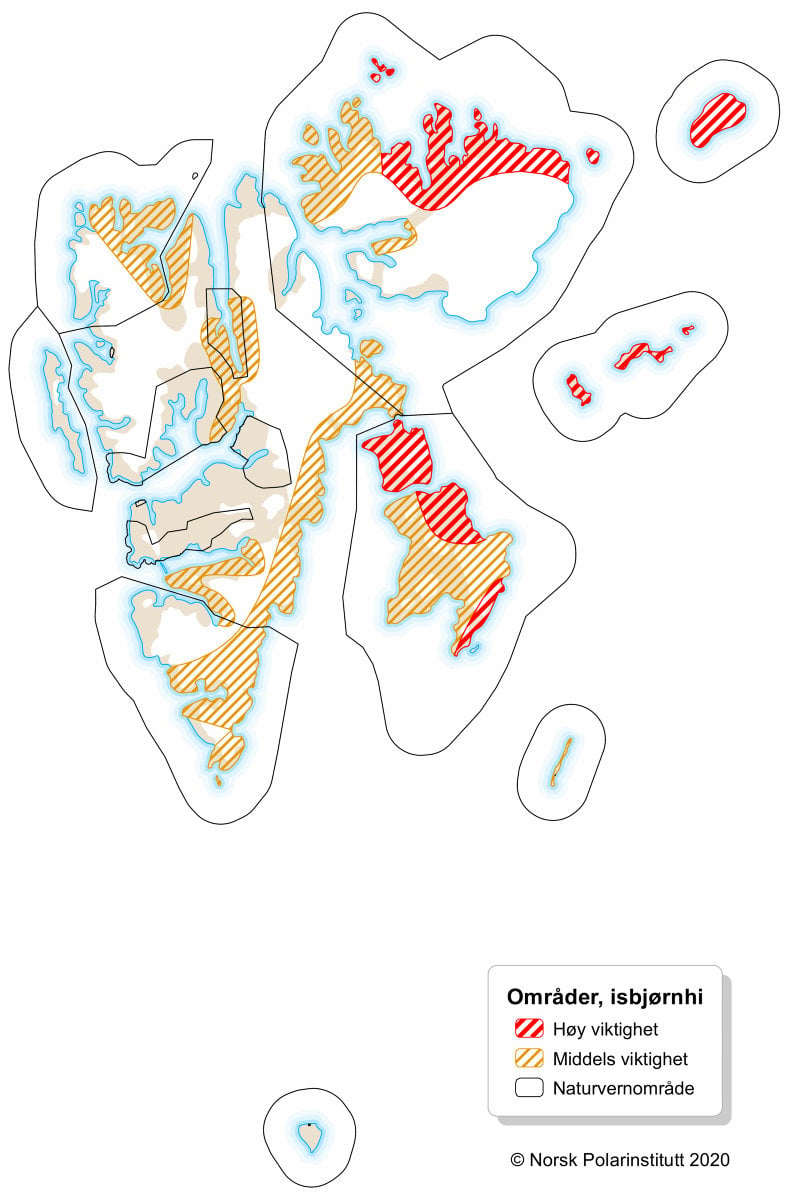

Good denning areas then and now

In 1939, Kongsøya, an island in eastern Svalbard, was protected because it was found to be a very important breeding ground for polar bears. Its topography, with steep mountain sections, and location in an area of almost year-round sea ice, made it a favourite area for female bears to hunt in the ice. The neighbouring island of Svenskøya has also been a good denning area. Further south we have Hopen. This island was not seen as a good denning area a few decades ago, but, in the 1990s, scientists found that it was more important than previously assumed, with tens of cubs in good years.

Common to all three islands is that they become isolated both from other parts of Svalbard and from the ice edge when the sea ice is scarce. Scientists found that significant numbers of polar bears made it to Hopen only in years when the ice around the island formed before mid-November. In recent years, such ice formation is the exception, and Hopen is no longer considered a good denning area for polar bears in the Barents Sea.

In recent years, much the same has happened on Kongsøya and Svenskøya. Here, where there may have previously been ice almost all year round, ice is recently often scarce until mid-winter. There is a correlation between how late the ice arrives around Hopen and Kongsøya in the autumn, and how many dens are observed the following year.

For the three islands mentioned, the Norwegian Polar Institute, along with Glen Liston of the University of Colorado, has evaluated a model that correlates where snow will settle in sufficient quantity in the autumn with where polar bear dens actually occur. The model uses terrain data and weather data (wind and snow) to say how snow is distributed in the terrain.

Caption: Yellow pixels show where the model predicted that there was enough snow for bears to den, and black symbols where dens were actually observed, from the west of Kongsøya in the winter of 1978-1979.

Positions from known dens show that the model works very well. We can accordingly produce a map that indicates which areas are suitable for polar bears. This can then be used in studies that search for polar bear dens in order to investigate den ecology, both in respect of the importance of different areas for breeding, and for behavioural studies.

The whole of Franz Josef Land has been mapped using this tool. Colleagues from Russia who work on the same population as us (the Barents Sea population) are now undertaking den studies there.

Yellow pixels show where the model predicted there was enough snow for females to den, and black symbols where polar bear dens were actually observed, from the west on Kongsøya in the winter of 1978–1979. Figure: Merkel et. al 2020, Polar Research

Local polar bear versus pelagic polar bear

There are polar bears that live in Svalbard all year round (local polar bears) and polar bears that migrate between the sea ice edge where they hunt and the islands where they go to den (pelagic polar bears). Local bears in Svalbard do not face such big challenges in finding a denning area. There needs to be enough snow, but they do not have to migrate over long distances. The biggest challenge for these bears may be to accumulate enough fat on their bodies before denning, now that the sea-ice-free periods, with less access to seals, are longer than before.

Deployment of cameras with motion sensors outside a polar bear den. Collaboration with Polar Bear International. Photo: Kt Miller/@ktmillerphoto

The pelagic bears face different challenges. They are probably well-fed throughout summer, since they hunt up in the ice. But the stretches of open sea between the ice edge and Svalbard in the autumn now often reach several hundred kilometres. In the past, they could almost always get there on the sea ice. Polar bears are good at swimming, and can actually cross stretches of several hundred kilometres. But this takes a lot more energy than travelling on the ice. Denning females can rarely afford to consume a lot of the fat reserves that are intended for feeding their cubs. As a result, we do not see many female bears in dens on Kongsøya and Hopen in years when the sea ice does not form around the islands in autumn.

Difficult years

What happens to polar bears in those years when there is little ice around traditionally important denning areas such as Kongsøya and Hopen? Will many females that would normally have cubs fail to den in those years? And will this mean a sharp reduction in population growth?

We still don’t know the answer. It may be that bears that normally den on Hopen and Kongsøya go to den elsewhere, either in north-east Svalbard, or in Franz Josef Land. Population estimates from 2004 and 2015 do not indicate that there were fewer bears, so we think polar bears are good at finding alternative areas if they have to.

Recording of polar bear dens on Kongsøya in 2009. Polar bear researcher Thor Larsen and senior adviser Øystein Overrein used the “Bjørnehiet” hunting cabin as their base. After three weeks, Jon Aars replaced Thor Larsen. They observed 25 certain and 7 possible dens, and recorded litter sizes. Similar surveys were last made in 1985, and were also subsequently carried out in 2011. Photo: Øystein Overrein, Norwegian Polar Institute

There’s no place like home

We know that some polar bears that have had satellite collars fitted have denned in the east of Svalbard in one year and in Russia’s Franz Josef Land in another year. In other words, they have both Norwegian and Russian cubs. Nevertheless, genetics show that close relatives den locally within very restricted areas, such as the south or north of Hopen. This suggests that, when they grow up, female bears prefer to return to the area of their birth, and do so year after year, if they can. But if the ice conditions make this difficult, they may go and den many hundreds of kilometres away.

Data from collars shows that the local Svalbard bears are exceedingly steadfast in selecting denning areas. Mothers and daughters tend to den very close to each other, and a female is likely to place her den within a few kilometres of where she has previously denned. This is probably very advantageous, because they know, firstly, where to find a good area without having to search and, secondly, the route from there to good hunting areas for replenishing themselves after a long winter.

A female with two cubs has left the den. Photo: Øystein Overrein, Norwegian Polar Institute

Future

Most evidence suggests that the polar bear population around the Barents Sea, including Svalbard, is still doing well. Models show that more snow can be expected in eastern and northern areas in the coming years, but less in south-west Svalbard.

Less snow may well present challenges for polar bears on the island of Spitsbergen in the future. Polar bear dens that have collapsed in mild weather have been observed, and a lack of snow may also mean less well-insulated dens. However, a greater challenge is more likely to be the continuing reduction of sea ice. Due to longer distances between the hunting areas on the ice edge and the denning areas, the female bears will have difficulty reaching their dens, or will have to expend more energy to get there (making it harder to feed their cubs). Equally, the return trip from den to ice edge may be difficult with cubs if there is also little ice in spring.

We believe that Franz Josef Land will become a more important denning area in the years to come, at the expense of Svalbard. It is much colder around these islands and the distance to the ice edge tends to still be short, if indeed there is any open sea around the islands.

Franz Josef Land today is rather like Svalbard 20-30 years ago. But sea ice conditions around Franz Josef Land have also changed in recent years and, if this continues, the Barents Sea population of polar bears may face a huge challenge in a couple of decades. If it proves too difficult for the bears to reach the islands of Franz Josef Land, there are no remaining options. There are no other islands further north.

See the research article in Polar Research.

Female with two cubs hunting in the drift ice in Hinlopen Strait. Photo: Janne Schreuder, Norwegian Polar Institute

See also